Reel Beach: Glen Stewart Ravine is our oasis in the city

By BERNIE FLETCHER

A community newspaper keeps us informed about events in our neck of the woods such as the Protect Our Ravine Rally on Aug. 11. Glen Stewart Ravine is designated an Environmentally Significant Area and nature’s health truly is our health.

Last year in Beach Metro Community News I found out about a screening of the moving film The Boy in the Woods at the Fox. In an article by Erin Horrocks-Pope, the director of the movie, Rebecca Snow, said: “Walking through the old growth forest in Glen Stewart Ravine and along the beach just feeds all the creative juices. We’re so lucky here to have these connections to real, raw nature in an urban centre.”

As kids, the ravine was our playground for adventure and imagination.

We roamed the hills and splashed in the creek. We learned sports in the park by Glen Manor Drive which once was part of a much larger ravine and riverbed which stretched from above the Danforth to the lake.

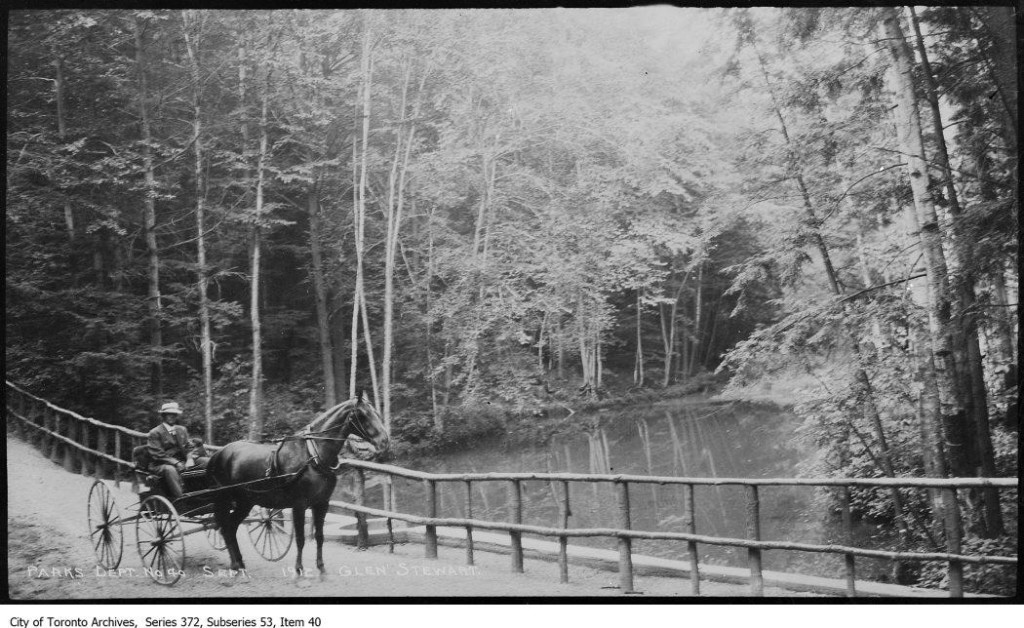

Many a Beacher learned to skate where ducks used to swim on ponds. The ravine was given to the city as a park in 1931.

In 1894 the Globe extolled the virtues of a new electric streetcar line along Kingston Road claiming “the fascination of the Witches’ Park at East Toronto will greet you with its beauty cup”.

On a 1903 map the ravine is marked “the Glen”. It could also have been called Glen Duart, but the city named it Glen Stewart after the estate and golf course of A. E. Ames. Glenn and Jean Cochrane referred to it as “the Naitch” or Nature Trail. We just called it the ravine.

Toronto ravines were a place of refuge for a troubled character like Harry Trotter in Morley Callaghan’s first novel, Strange Fugitive (1928).

The book is considered to be the first gangster novel in North America. It tells the story of a violent anti-hero who loses his job and becomes a bootlegger and mobster.

In better times Trotter and his wife liked to picnic and relax in “a wooded ravine with a slow twisting river” beyond the eastern city limits as “the Kingston Road radial car away to the south-east hooted mournfully”. The couple walked along railroad tracks so I would guess this was Taylor-Massey Creek and Warden Woods.

I usually write about films that were actually produced, but Callaghan’s book never made it to the screen.

Hollywood studios considered Strange Fugitive as a film in 1930. Warner Brothers thought of having James Cagney play Trotter, but opted for Little Caesar as the first of many gangster films leading all the way up to The Godfather.

The dark mood of film noir became a popular genre in the 1940s.

Morley Callaghan (1903-1990) grew up in Riverdale, attending Withrow Public School and Riverdale Collegiate Institute. While a young reporter for the Toronto Star in 1923 he became friends with fellow scribe Ernest Hemingway.

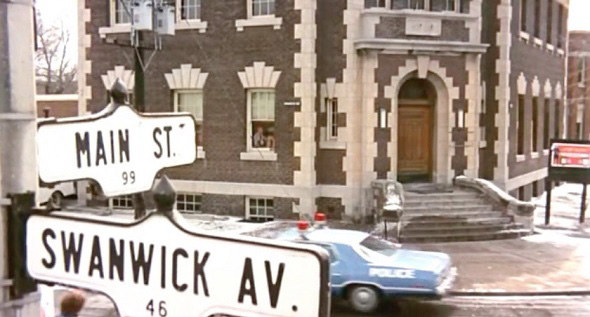

Callaghan covered stories about the ugly underbelly of the city of churches “Toronto the Good”: speakeasies, rum-runners and gangsters who controlled the bootlegging trade in the Prohibition Era. In one incident police shot and killed a man on a smuggling schooner at Ashbridges Bay.

Spending time in Paris, Callaghan soaked up the literary atmosphere. His memoir, That Summer in Paris, includes the infamous 1929 boxing match where he knocked down Hemingway who blamed F. Scott Fitzgerald, the time-keeper of the bout.

The memoir was adapted into a 2003 CBC mini-series Hemingway vs. Callaghan with Gordon Pinsent as Callaghan looking back at that long-ago summer.

In 1958 four of Callaghan’s short stories were adapted into the film Now That April’s Here.

The natural beauty of Glen Stewart Ravine has inspired painters William Kurelek and Doris McCarthy (both of Balsam Avenue) as well as naturalists Fred Bodsworth (Last of the Curlews) and Dr. Fred Urquhart (Flight of the Butterflies).

“The people in the Beach always stick together.”

Director Norman Jewison

Don’t mess with Beachers! In 1907 we came together to stop a proposed railway line that would tear through the beachfront. Can you imagine?

The 1950s and 1960s saw a Save the Ravines movement in Toronto, including opposing a big apartment on the edge of our Glen Stewart. The community rose up against the Scarborough Expressway and a 22-storey building planned for Lee Avenue as well as rallying to save the Leuty Lifeguard Station.

We all need to stand up and defend our natural green spaces for the health of ourselves and future generations.

We only have one earth. Let’s take care of it.

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.