Toronto Typewriters on Carlaw Avenue – a celebration of the carriage, the ribbon and the bell

By ANNIE ROSENBERG

Nestled at the junction of Carlaw Avenue and Queen Street East sits Toronto Typewriters, where proprietor Chris Edmondson has been serving typewriter enthusiasts since 2014. Here, collectors, nostalgia seekers, and digitally weary souls can buy, repair, or rent a humble typewriter.

“I’ve always been fascinated by mechanical objects,” said Edmondson. “As a kid, I’d tinker with my toys, finding interesting objects. Later, it inspired me to get a typewriter and I was instantly hooked.”

His first typewriter was a sky blue Brother Opus rescued from a Value Village. “I knew nothing about it, but it was so cool I had to have it. When I discovered that there weren’t any outlets for typewriter enthusiasts in Canada on a large scale, I realized there was an opportunity.”

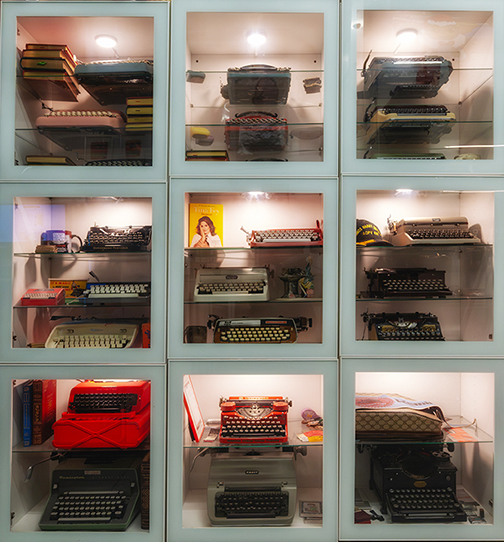

Once considered obsolete, today, typewriters are ubiquitous. For Edmondson’s customers, writing machines are anything but outdated pieces of machinery — they’re practical and cherished possessions, each one telling a singular story: one types in Hebrew characters, another in Cyrillic script, yet another types out music notes.

Decked out in overalls and a black T-shirt, clutching a screwdriver in one hand, Edmondson moves through the shop, where rows upon rows of typewriters rest in their cabinets: a mid-century Italian Olivetti Lettera DL; a vintage 1930s Remington Portable 3; a 1940s Hermes Media revealing their workings: platens and ribbons; knobs and paper balls; levers and keys and carriages.

“We get a lot of people who grew up with typewriters—people from all walks of life who have been recognized for the gift of the gab—writers, songwriters,” he explained. “But most exciting are the kids and teenagers who’ve grown up with computers because they haven’t been exposed to such tactile machines. They’ve only seen typewriters on TV.”

He pulls a spool of ribbon off a hook.“We have black, red, purple, blue, and two-tone red and black ink. Our writing machines are the primary products, but we also sell ribbons.”

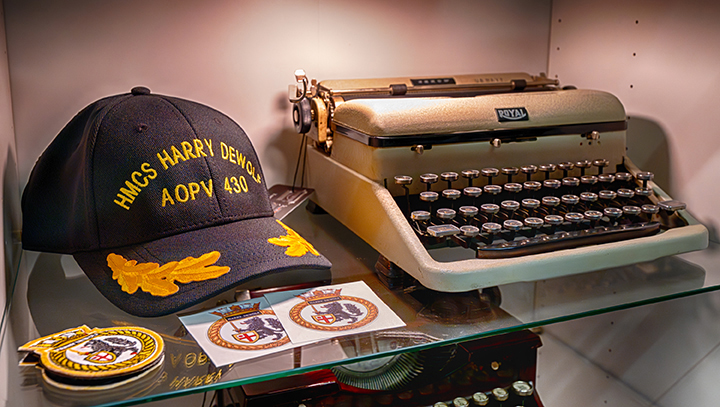

The shop boasts a cornucopia of typewriter-themed merchandise: tiny candles molded into Underwood typewriters, a “Praise the Word” typewriter mug imprinted with typewriter letters, a typewriter post-it notes dispenser complete with a “Pull Me” tab. Perched above a display case is a framed picture of an orange typewriter sandwiched between two red ones.

On the highest shelves rest wooden shipping crates: Smith Corona Typewriter! one proclaims. On a lower shelf sits a Marvel typewriter, described by Edmondson as “A typewriter with an unknown mysterious origin, perhaps belonging to a superhero or masked vigilante?”

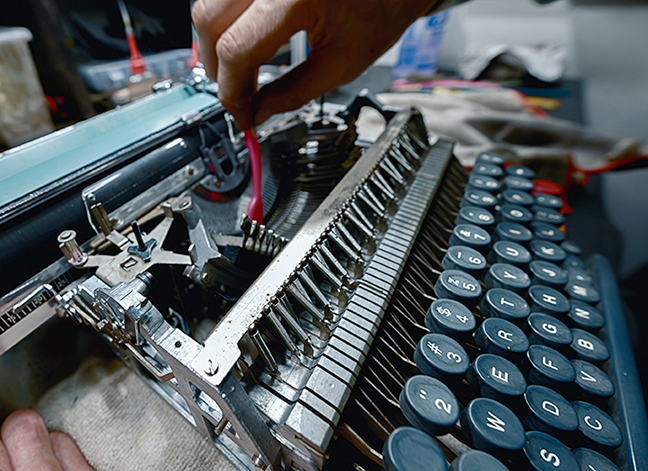

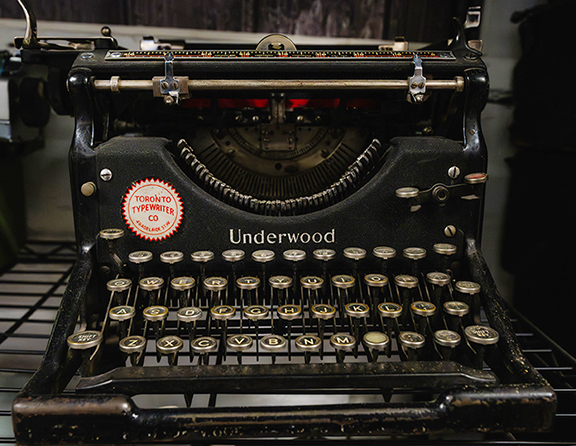

At the back of the shop, his aide, Jeffrey, tends to an Underwood.

“There’s a basic set of tasks that we do,” he said. “First, we clean each one and then test it. They deteriorate from lack of use, so they need a certain kind of attention to bring them back to life.”

He unclasps the plastic shell, exposing its innards. “Some of them have been stored in garages for years collecting dust,” he said, reaching for the air compressor hanging beside him.

“Usually the problems reveal themselves, but sometimes you have to dig a little because typewriters are as delicate and quirky as people…One of them even had a dead mouse inside; it had been sitting in a barn.”

Edmondson pops the lid on a black Royal Deluxe from the 1930s. “People used typewriters for decades—they were built to last. Everything nowadays is built to break.”

“There’s a perfect typewriter for everyone,” he said. “They’ll find a machine, try it out, and say, ‘This is it. This is the one.’”

He pauses in front of an Olivetti Valentine designedby Ettore Sottsass. La rossa portatile—the red portable—boasts a dramatic presence: glossy red bodywork, red swing handle, white letters atop black plastic keys, orange spool caps announcing themselves. “An object that one carries with him like one wears a jacket, shoes, or hat,” Sottsass once said of his creation.

“If you look at some U.S. typewriters, a lot of them were used by accounting departments and bean counters—a means to an end,” said Edmondson. “But the Valentine is an icon of industrial design. It was meant to be a companion for free-spirited artists and writers.”

Typewriters have shaped a significant part of literature — companions to such luminaries as Mark Twain, whose Life on the Mississippi was the first literary work completed on the machine. And William S. Burroughs believed that a writing machine he called the “Soft Typewriter” was writing our lives and books into existence.

Edmondson is equal parts salesman and repairman, historian and therapist. “Sometimes people come in with a typewriter they want to sell that belonged to their mother or father. They’ll sit on the couch and open up, share their stories.”

He walks over to a 1950s Royal Futura, wiping off the keys, cultivating the sound and fury of bygone days: the hunt and peck, the slide and clatter, the ting! of the bell rising up to the ceilings of smoky offices and typing pools; of newsrooms and living rooms; writers and poets, reporters and secretaries, furrowed brows and ruby red nails straining to reach the Q, turning letters to language under their fingertips.

Edmondson separates two stuck keys. “Typewriters are vessels for capturing people’s existence. They force you to write with intent because there are no prompts or pop-ups, so there’s more awareness of what you’re doing.”

He leans over an Olympia, inspecting the array of letters, tapping the “C,” the “L, the “A,” metal keys striking ribbon, letters leaping up to meet paper, the percussive rhythms rising and falling through the little shop on Carlaw.